The market-based solution to California's water crisis

Prescriptive government is the opposite of what we need

California is battling a devastating drought, and the Golden State's heavy-handed Democratic administration has an ill-conceived plan to use aggressive government regulations to save the day. Not only is this wrong, but it won't actually do much to solve the water crisis afflicting California, which requires less — not more — government intrusion in people's lives.

The standard narrative about California's crisis is that three rainless years have depleted the state's major water reservoirs, thinned the snowpack, and dried up the rivers, causing a massive water shortage that requires mandatory cuts in water use.

However, as the young proverb goes, nature makes droughts, but men make scarcity. In this case, the scarcity is the result of a cascading series of poor policy decisions by government officials. Chief among the problems is cheap, below-market water prices for everyone — but especially politically favored groups.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Among the most favored are environmentalists who have forced the state to abandon critical water-storage reservoir projects to avoid disruption of wildlife and ecosystems. But that's not all they've done. They also divert 4.4 million acre-feet of water every year — enough to supply the same number of families — to restore water runs such as the San Joaquin River, allowing passage of salmon and other fish. Without paying a dime, environmentalists have taken control of nearly half of California's water.

Of the remainder, 80 percent goes to farmers, the next most favored group — even though their output is only 2 percent of the state's GDP. Farmers don't pay anywhere close to market prices because many of them have inherited their surface water rights from their ancestors, thanks to California's system of "first come, first served." Under those rules, farms that first drew water from a river or some primary source have the right to that amount of water in perpetuity. Newer users get the leftovers, depending on when their ancestors called dibs.

This wouldn't be so bad if senior users could sell their surplus water to those who needed it. But that's not how it works. Instead, what they don't use one year, they lose the next — creating a massive incentive for overuse.

What's more, many farmers and property owners pay nothing but the cost of a well to draw groundwater — and even that is sometimes subsidized. The upshot is the classic "tragedy of the commons," with farmers in the Central Valley able to suck out water to their heart's content, endangering aquifers.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In other areas, you do have to pay for water — but the pricing is extremely skewed. Farmers in California's Imperial Irrigation District, who buy water from the Colorado River aqueduct, pay $20 per acre-feet, less than a tenth of what it can cost in San Diego. And it's all thanks to sweet deals they've obtained from the government.

Cheap agricultural water has led to the insanity of a desert like California becoming one of the world's chief producers of water-intensive crops, such as rice and alfalfa. George Mason University economist Alex Tabarrok estimates that if farms used just 12.5 percent less water, California could increase the amount available for industrial and residential use by half.

And although residential users pay more for water than farmers, they still pay below-market prices. Sacramento homes pay a flat rate for their water, no matter how much they consume. They don't even have meters. In Fresno, which gets less than 11 inches of rain a year, monthly water bills for families are sometimes only a third of those in Boston, which gets four times more rain.

The best — and most sustainable — solution to California's water woes would be full-bore markets in which prices can rise and fall with supply and demand. Under such a system, depleting water reserves would have led to price increases long ago, producing an automatic incentive to conserve. More importantly, this would have clearly signaled growing scarcity, spurring new technologies for affordable water generation. All of this would have allowed consumers and businesses to make small adjustments over time without letting the shortage reach a crisis point.

Moving overnight to a system of market-based water pricing is probably not doable. But if California has to make emergency cuts, it would make sense to impose the biggest cuts on the biggest users — which means the deepest cuts for fish-rescuing environmentalists, followed by water-hogging farmers, followed by residential users. Instead, Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown is doing the exact opposite.

Brown wants to cut the state's overall water use by 25 percent. But what do environmentalists have to contribute to that goal? Nothing. Nada. Zilch.

In fact, nature's protection has assumed such religious significance that California's legislature has handed the Department of Fish and Wildlife near-God-like powers to penalize violators engaging in any "unauthorized diversion of use of water that harms fish and wildlife resources." This could expose tens of thousands of farmers and ranchers to daily fines of $8,000 for reservoirs and culverts that already exist — just because the state now deems them to be obstructing the passage of fish, Steven Greenhut reports.

Farmers, by contrast, are required to cut water use — but only by 6.6 percent. City dwellers are the ones getting slammed — even though they pay the most and use the least.

The Brown administration is using executive fiat to impose a strict and intrusive water diet on them. Restaurants are barred from serving water until specifically requested by customers. Homeowners are banned from hosing down driveways or cars, with some violators facing fines of up to $500 a day. The rich folks in Beverly Hills, Newport Beach, Palos Verdes and other parts of Southern California are being targeted particularly fiercely. "The idea of your nice little green grass getting water every day, that's going to be a thing of the past," Brown declared, positively gleeful. These areas are being ordered to swallow a 35 percent cut. But sacrificing the lawns of the rich is less about conservation and more about enforcing virtue.

California is engaging in counterproductive favrotism based on totally subjective value judgments of which type of water use is right and which is wrong that have little to do with people's real needs. It's time to let the market make these decisions instead.

Shikha Dalmia is a visiting fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University studying the rise of populist authoritarianism. She is a Bloomberg View contributor and a columnist at the Washington Examiner, and she also writes regularly for The New York Times, USA Today, The Wall Street Journal, and numerous other publications. She considers herself to be a progressive libertarian and an agnostic with Buddhist longings and a Sufi soul.

-

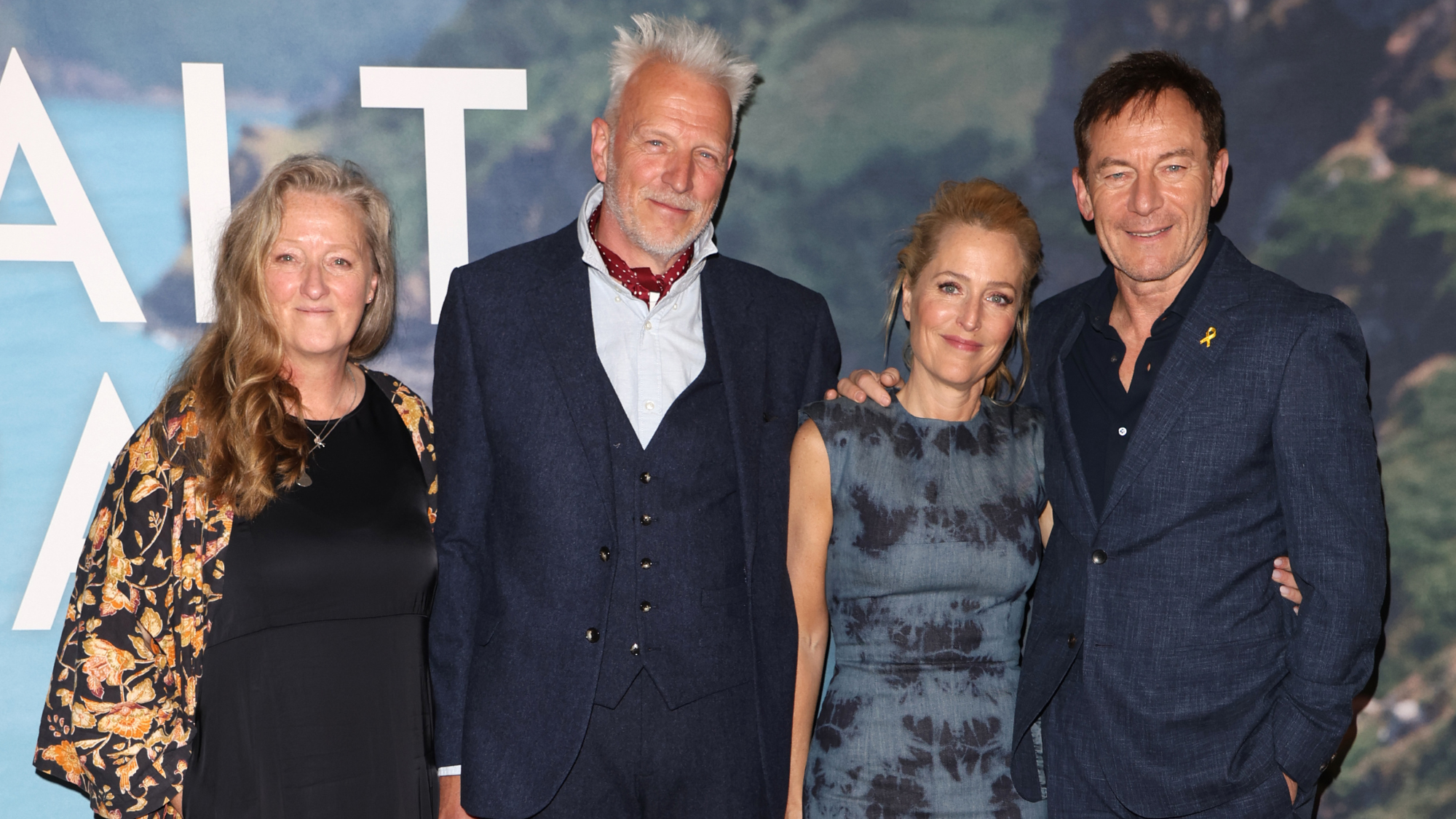

The Salt Path Scandal: an ‘excellent’ documentary

The Salt Path Scandal: an ‘excellent’ documentaryThe Week Recommends Sky film dives back into the literary controversy and reveals a ‘wealth of new details’

-

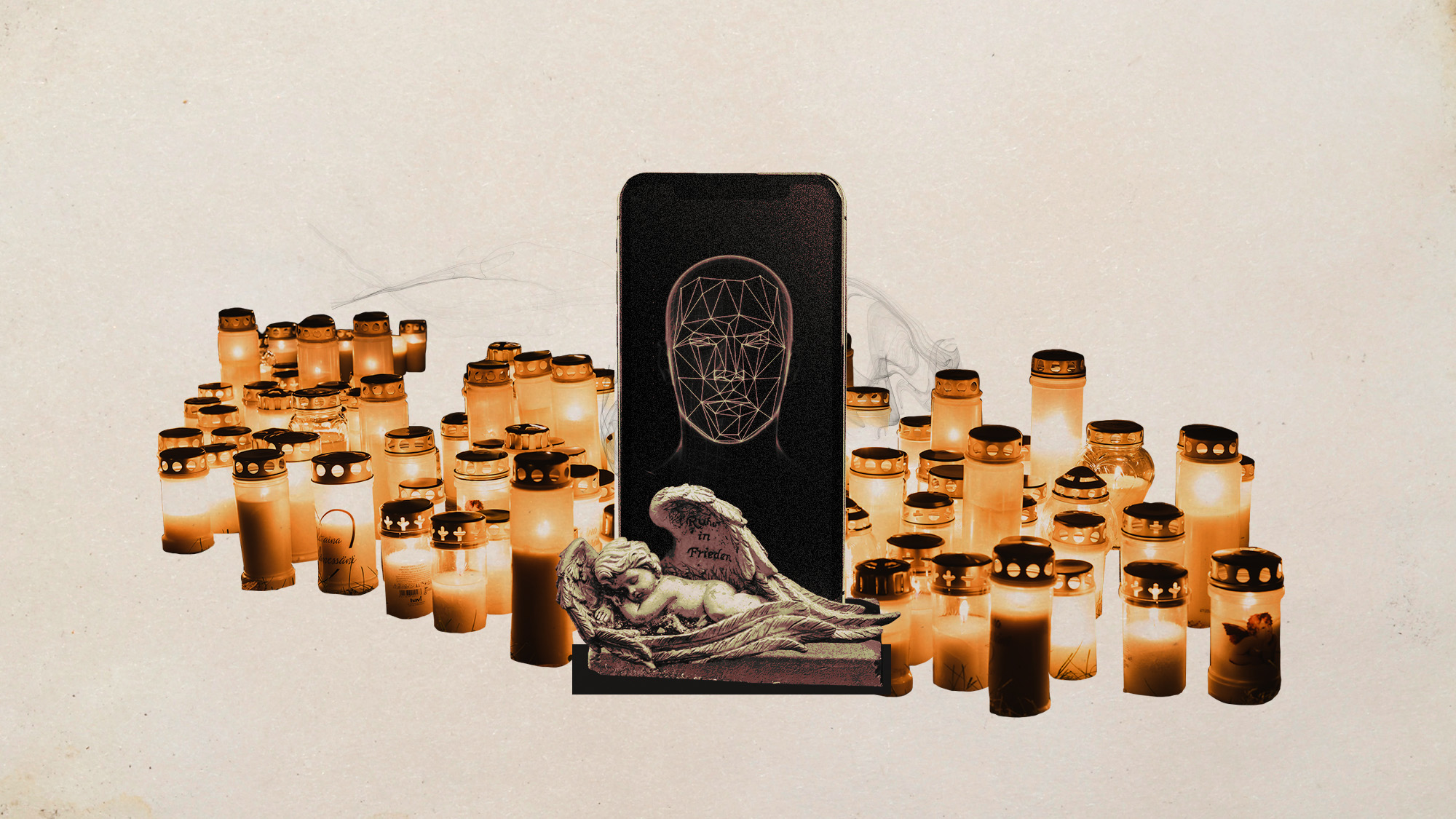

AI griefbots create a computerized afterlife

AI griefbots create a computerized afterlifeUnder the Radar Some say the machines help people mourn; others are skeptical

-

Sudoku hard: December 17, 2025

Sudoku hard: December 17, 2025The daily hard sudoku puzzle from The Week